You are in „Things and Concepts“

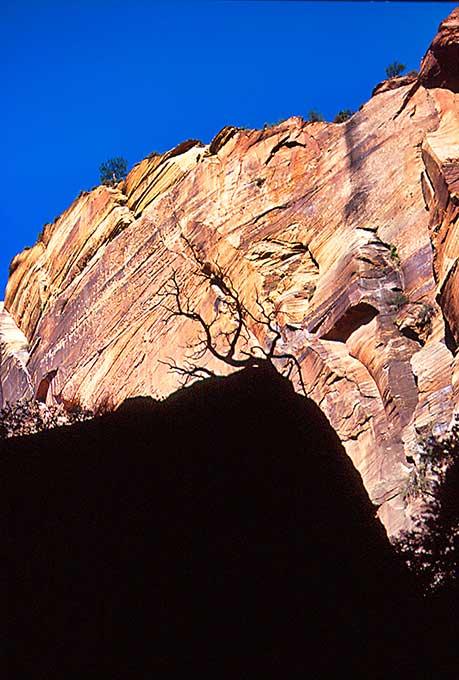

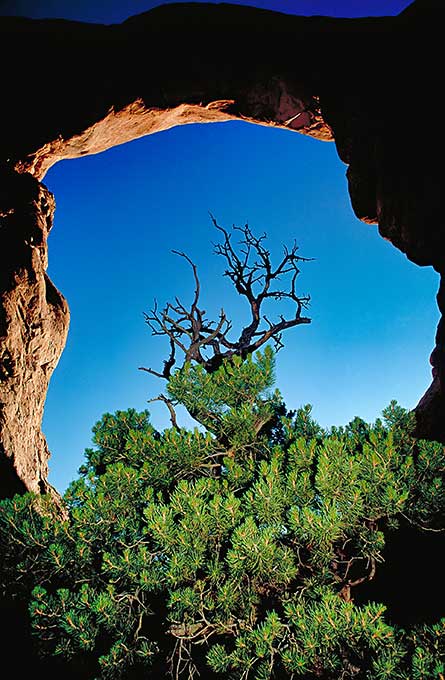

„In nature, nothing is perfect and everything is perfect. Trees can be distorted and bent in the strangest ways and they’re still beautiful.“

Alice Walker (9)

Psychology professors Ruth Richards and Christine Kerr showed people all over the U.S. pictures of natural scenes, clouds, coastal views, and trees, each in pairs with few and many fractal features. No matter where they conducted this test, the images with many fractals were the most popular because, as the subjects indicated, they evoked feelings of peace, calm, serenity, and naturalness. The second step was to provide more precise information about the preferred degree of fractal dimensionality. Therefore, five computer-generated images of different complexity were used in each case. In this experiment, the trend of preferring more fractal features did not continue. Instead, the majority of judgments settled on scenes of medium dimensionality, at or slightly above the value Benoit Mandelbrot had attributed to the natural world (2).

Nature, then, obviously holds an aesthetic experience because pattern formation in it follows a universal law and develops into fractal dimensionality. Up to a certain point, the higher this dimensionality, the more pronounced our aesthetic experience.

Universality and infinity are concepts that Immanuel Kant already associated with aesthetics. Kant’s analysis of the aesthetic, particularly in the analytical part of the Critique of Judgment, continues to spark significant interest today and has proven to be beneficial for comprehending modern art. According to Kant, the determination of the aesthetic is a subjective process of cognition in which the power of judgment assigns the predicate „beautiful“ or „not beautiful“ to an object. Such judgments of taste must meet certain criteria, including independence from any personal interest, subjectivity, general validity, and necessity. As in ethics, Kant thus looks for the formal criteria of a judgment and excludes the substantive determination of the beautiful. Most importantly, he distinguishes between the beautiful and the sublime, ascribing to both categories their own important properties.

The definition of „the beautiful“ is „that which presents itself without concepts as the object of a general benevolence“. The beautiful does not refer to the individual inclination of the subject and must therefore contain a reason for pleasing everyone; therefore, we have reason to expect a similar pleasure from everyone“. What is merely pleasing to an individual may be pleasing (e.g., a particular color or a single tone), but it is not beautiful. The judgment of taste presupposes „universal rules“, even if the generality here is „subjective“ (i.e., as a general-subjective reaction to the beautiful object), provided that it is not based on a concept but on a feeling and is to be called „commonality“. The state of mind in the „free play of imagination and understanding“ is the condition and basis of this generality: a „purposiveness without purpose.“ The judgment of taste becomes „pure“ only when it expresses this purposefulness of form without „stimulus“ or „emotion.“ Against Leibniz, Baumgarten, and others, aesthetic judgment depends only on the ‚unanimity in the play of the forces of mind‘ (prompted by the object) and not on the perfection of an object.“

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason

„The sublime, in contrast to the beautiful, is also found in the formless, unbounded. Furthermore, it carries with it a „movement of the mind.“ Sublime is, „what is par excellence great“, „what is great beyond all comparison“. The extension of the imagination into the great is here the pleasing, in that the „inadequacy of our ability to estimate size“ awakens the feeling of a „supersensible ability in us“. Thus, the sublime is defined as „what even our ability to think proves, a faculty of the mind that surpasses every measure of the senses.“ Here, the power of judgment relates the power of imagination to reason, the supersensible, and the infinite. Nature appears sublime in those phenomena whose contemplation „carries with it the idea of their infinity,“ which thus leads the concept of nature to a „supersensible substrate“ that puts us in a sublime mood of mind. The superiority of our reason, which can think the infinite, over the most violent of nature, is the reason for this mood of mind.“

Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason

„Nature seems to have left out no opportunity for ornamentation. Think of the trees in winter and the patterns of their branches against the sky; how the bare branches spread out beneath the mighty sea-grass cover in the calm water. To see them frost-covered or fresh after a snow shower is a revelation of their beauty. In spring, when they begin to bud and glow with color, they seem even more like sea grass than usual. And if you get close enough to distinguish them from one another, the individual fresh shoots always have a character all their own and special beauty to match.“

Lewis Foreman Day, Nature and Ornament

Previous A new geometry

(1) Halsall, Francis, Chaos, Fractals and the Pedagogical Challenge of Jackson Pollock´s „All-Over“ Paintings: Journal of Aesthetic Education, Vol. 42, No. 4, Winter 2008, S. 16

(2) Richards, Ruth, A New Aesthetic for environmental awareness: Chaos Theory, the beauty of nature and our broader humanistic identity, Journal of Humanistic Psychology, Vol. 41 No. 2, 2001, S. 59-95

If you found this post useful and want to support the continuation of my writing without intrusive advertising, please consider supporting. Your assistance goes towards helping make the content on this website even better. If you’d like to make a one-time ‘tip’ and buy me a coffee, I have a Ko-Fi page. Your support means a lot. Thank you!

Since I started my first website in the year 2000, I’ve written and published ten books in the German language about photographing the amazing natural wonders of the American West, the details of our visual perception and its photography-related counterparts, and tried to shed some light on the immaterial concepts of quantum and chaos. Now all this material becomes freely accessible on this dedicated English website. I hope many of you find answers and inspiration there. My books are on

Since I started my first website in the year 2000, I’ve written and published ten books in the German language about photographing the amazing natural wonders of the American West, the details of our visual perception and its photography-related counterparts, and tried to shed some light on the immaterial concepts of quantum and chaos. Now all this material becomes freely accessible on this dedicated English website. I hope many of you find answers and inspiration there. My books are on