You are here: Nature Science Photography – Image creation, Depth and Size – Space perception

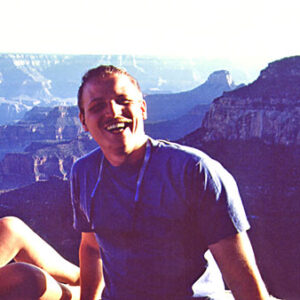

Atmospheric perspective (also known as aerial perspective) is due to the fact that we perceive more distant objects as distorted in terms of sharpness and detail as well as brightness and color. The diminishing sharpness and the increasing blueness or brightening of all tonal values with distance are two criteria from which our visual system infers distance and spatial depth based on experience. They are therefore learned.

„There is a kind of perspective called aerial perspective, which depends on differences in the density of the air. (…) Seen through dense air – as you can see in the case of mountains, for example – every object appears bluish. (…)“.

Leonardo da Vinci in his writings on the art of drawing

The reason for the formation of the air perspective lies in the nature of the atmosphere. It contains particles of different sizes, such as dust, water droplets, gases and aerosols. These cause what we call haze through a physical process called Mie scattering after its discoverer. Gustav Mie’s calculations predicted in 1908 that regularly shaped particles whose diameter is larger than the wavelength range of visible light (400 to 700 nm) will scatter incident radiation more and more just forward as their size increases, and more and more uniformly across the entire spectrum. „Forward“ in this case means opposite to the direction from which the light is incident, and „uniform“ means that no wavelength range is favored and all colors complement each other to form a more or less distinct white.

Since scattering is a kind of „blurring“ of light, as distance increases, detail is lost and our perception of sharpness fades. Objects in the middle distance are particularly affected by the scattering of the short-wave blue or the UV part of the spectrum and therefore often appear dull, faded and too blue. With still further increasing distance (the more powerful the intervening air layer is) the effect of the Mie scattering increases more and more. That is why the sky appears white to us where it is farthest away from us on the horizon.

We often become aware of the effect of air perspective only when this clue is missing in areas with very pure air. There, even distant landscapes appear very close to us and we suddenly have difficulties in estimating the distances correctly.

Next Color perspective

Main Image creation, Depth and Size

Previous Central perspective

If you found this post useful and want to support the continuation of my writing without intrusive advertising, please consider supporting. Your assistance goes towards helping make the content on this website even better. If you’d like to make a one-time ‘tip’ and buy me a coffee, I have a Ko-Fi page. Your support means a lot. Thank you!

Since I started my first website in the year 2000, I’ve written and published ten books in the German language about photographing the amazing natural wonders of the American West, the details of our visual perception and its photography-related counterparts, and tried to shed some light on the immaterial concepts of quantum and chaos. Now all this material becomes freely accessible on this dedicated English website. I hope many of you find answers and inspiration there. My books are on

Since I started my first website in the year 2000, I’ve written and published ten books in the German language about photographing the amazing natural wonders of the American West, the details of our visual perception and its photography-related counterparts, and tried to shed some light on the immaterial concepts of quantum and chaos. Now all this material becomes freely accessible on this dedicated English website. I hope many of you find answers and inspiration there. My books are on